Sweeping narratives that provide an umbrella explanation for complex phenomena are always appealing, and farming and food in India offer a rich canvas for such tales. For decades, mainstream narratives framed the Green Revolution as the ‘saviour’ of Indian agriculture, transforming ‘underdeveloped’ farming methods through the introduction of ‘miracle seeds’ and modern technologies. The reality was far more nuanced. Post-independence policies, such as land reforms and increased investments in agriculture, contributed to rural development. They set the stage for the Green Revolution, whose benefits and adverse impacts varied greatly across geographies and communities. Decades later, millets are headlining a similar narrative, and enjoying a resurgence as superfoods that can fix multiple problems, from malnutrition and rural poverty to the climate crisis and biodiversity loss. They are being promoted as ‘sattvic’ foods and tools for women’s empowerment. But are these claims true?

This article aims to offer a more nuanced take, balancing these statements with humbler tales that depict the daily challenges and experiences of people who cultivated and ate millets. These tales describe what millets meant to these communities, why they transitioned away from them, and whether they can benefit from the millet revival.

Tales of scarcity and resilience

Tales of scarcity and resilience

In their village on the banks of the Sarayan river in central Uttar Pradesh (UP), North India, an elderly woman and her husband had conserved a unique variety of kodo (kodo millet, or Paspalum Scrobiculatum). They continued cultivating and harvesting this grain, even though other villagers considered them eccentric for following ‘outdated’ practices. I first met her in 2018, when I was accompanying farmer activists on a field visit. She quietly shared kodo millet seeds and rice, which she had hand-pounded herself, with us.

Millets, the resilient grains that had nearly vanished before being rediscovered, are inextricably linked to marginalized communities and forgotten traditions. They represent the ancient farming practices that were swept out of view by the Green Revolution. They also shine a mirror to the toil, tedium and oppression of the times when peasant communities were unable to exercise their rights.

About 2,000 km south of Shyamkishori, Dalit women in southern Karnataka share stories of their hard labour in the fields. Kadiramma described getting ragi mudde (balls of cooked finger millet flour) at the end of the workday. Ragi was their mainstay; they even picked out fallen grains from the fields after the harvest. After painstakingly cleaning the gleaned ragi, they had to give half of it back to the landlords. The pain and anger of those times were still carried in their voices more than 30 years on. “We worked from morning till night, and we women did the same heavy work in the fields as the men, but we were paid just enough to survive.”

About 2,000 km south of Shyamkishori, Dalit women in southern Karnataka share stories of their hard labour in the fields. Kadiramma described getting ragi mudde (balls of cooked finger millet flour) at the end of the workday. Ragi was their mainstay; they even picked out fallen grains from the fields after the harvest. After painstakingly cleaning the gleaned ragi, they had to give half of it back to the landlords. The pain and anger of those times were still carried in their voices more than 30 years on. “We worked from morning till night, and we women did the same heavy work in the fields as the men, but we were paid just enough to survive.”

Staving off hunger was a constant challenge for peasants and labourers from Dalit-Bahujan-Adivasi (DBA) communities, or the lower castes, who represented the oppressed at the bottom of rural hierarchies. The women of these communities learned to be extra-resourceful to feed their families. Alongside men, they cultivated multiple crops, including several types of millets, on their sandy, rocky and often undulating lands. These were the landscapes they had access to, as the fertile tracts were controlled by farmers from powerful castes. The produce from these fields was not sufficient to meet their needs.

DBA communities had knowledge of local ecosystems that allowed them to identify edible plants and animals, which they used in unique recipes that are rare to find in popular cookbooks. They also adapted and innovated. While rich and middle-income families roasted chana (Bengal gram) and jau (barley) to make sattu (malt) in the Gangetic plains, poorer families roasted cheaper grains. Today, nutritious foods like browntop millet are attractive to urban consumers, but in the past, they were foraged by DBA communities to stave off hunger.

DBA communities had knowledge of local ecosystems that allowed them to identify edible plants and animals, which they used in unique recipes that are rare to find in popular cookbooks. They also adapted and innovated. While rich and middle-income families roasted chana (Bengal gram) and jau (barley) to make sattu (malt) in the Gangetic plains, poorer families roasted cheaper grains. Today, nutritious foods like browntop millet are attractive to urban consumers, but in the past, they were foraged by DBA communities to stave off hunger.

Despite their resourcefulness, these communities often ran out of food grains in the lean seasons and had to go hungry or borrow money at usurious rates. This would leave them in a debt trap, whereby they would have to forfeit their harvest or work as bonded labourers in the lender’s fields to pay off their loans. Sadly, this state of affairs persists in some regions even today.

Tales of transformation and aspirations

Tales of transformation and aspirations

“We hulled and cleaned the paddy rice from the big farmers’ fields. But rice was for them, not for us,” remembered Venkatamma, in southern Karnataka. “I loved the sweet taste of rice. The ladies of the house monitored us closely to ensure that we did not make off with any, but I would pop some into my mouth when they weren’t looking. Sometimes, they gave us some rave (grits) to take home. How tasty our meals were in those days!”

Multiple routes contributed to improvements in the lives of DBA communities. Some received land titles in the 1970s and 1980s during the government’s poverty elimination campaign, while others gained land due to campaigns organized by Dalit, Adivasi, or Left-allied groups. Increased mobility led to migration and higher wages, which also drove up wages back home. People’s Movements campaigned for access to housing, education, nutrition and food security and livelihoods for marginalized communities, and successful campaigns led to improved quality of life.

As incomes rose, DBA households could now afford the foods of the rich—wheat and rice. The grains that they aspired to, which were only consumed on festivals and special occasions, were now accessible due to the Green Revolution. With the expansion of the Public Distribution System (PDS), wheat and rice were supplied at subsidized rates or even free of charge, resulting in a sharp drop in the consumption of millets from the 1970s onward. Even pulses were abandoned. These were cultivated alongside millets, but there was little place for them in the monocropped rice paddies and wheat fields. The diverse diets of DBA communities shrank to rice- and wheat-heavy meals deficient in protein and micronutrients. However, they could now eat to their hearts’ content and weren’t left hungry.

As incomes rose, DBA households could now afford the foods of the rich—wheat and rice. The grains that they aspired to, which were only consumed on festivals and special occasions, were now accessible due to the Green Revolution. With the expansion of the Public Distribution System (PDS), wheat and rice were supplied at subsidized rates or even free of charge, resulting in a sharp drop in the consumption of millets from the 1970s onward. Even pulses were abandoned. These were cultivated alongside millets, but there was little place for them in the monocropped rice paddies and wheat fields. The diverse diets of DBA communities shrank to rice- and wheat-heavy meals deficient in protein and micronutrients. However, they could now eat to their hearts’ content and weren’t left hungry.

Grain processing was another critical factor in shifting communities away from millets. Rice mills had begun to be set up in the late 19th century and, with government support, proliferated in the 1960s and 1970s. Meanwhile, millets, the grains designated as ‘coarse’ even by scientists, were ignored. In the absence of processing technology, these grains were processed mainly by hand until the 1990s and 2000s, when renewed interest led to the development of machines specifically for them. Women describe a range of traditional techniques used to dehusk barnyard, foxtail, little, kodo, and browntop millets, all of which required skill and patience. They welcomed the arrival of processed white rice and atta (wheat flour). However, the new grains were less nutritious than their traditional variants and were further stripped of their bran, which contains fiber and micronutrients. The bran was monetized, with rice bran sold for oil and wheat bran as an additive to fodder. This allowed rice and wheat to be sold at an affordable price, and nutrition loss became a secondary concern to consumers.

Thus, the aspirations of DBA communities, and even more prosperous ones, were met by policy and technology. Millets, associated with an oppressive and laborious past, were abandoned, and their near-disappearance was largely welcomed.

Tales of the millet revival

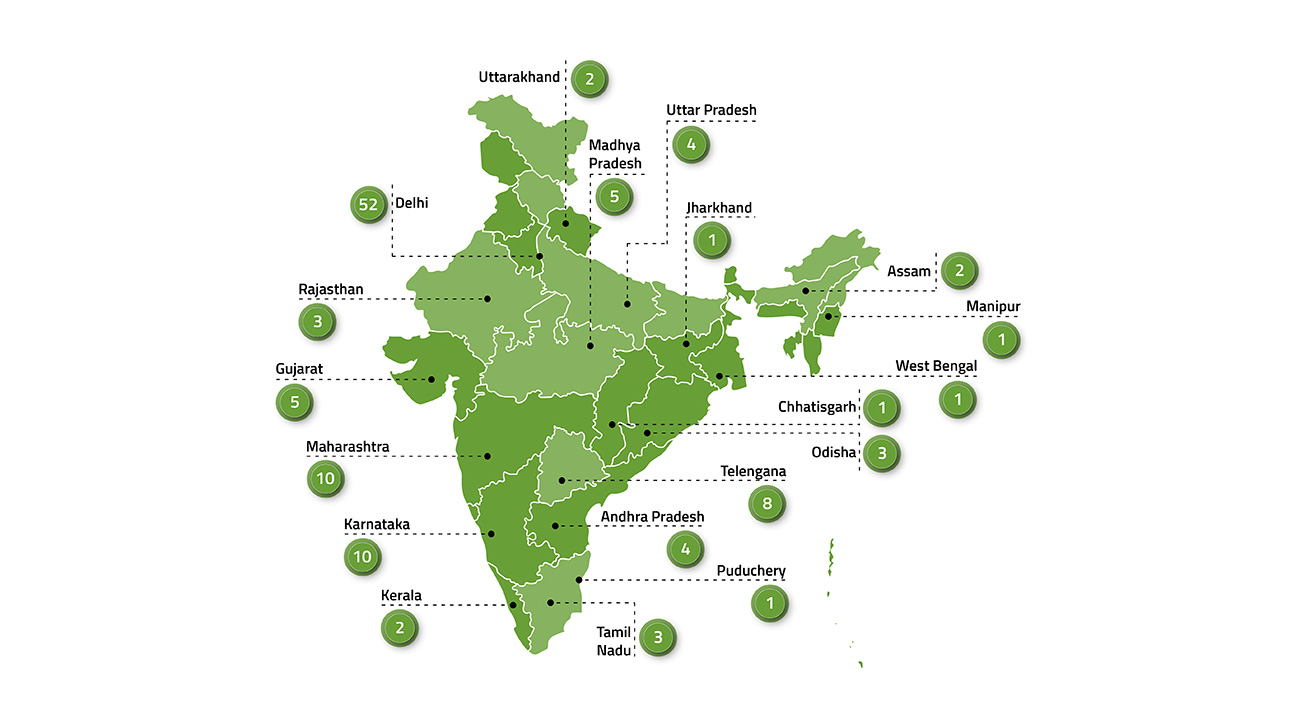

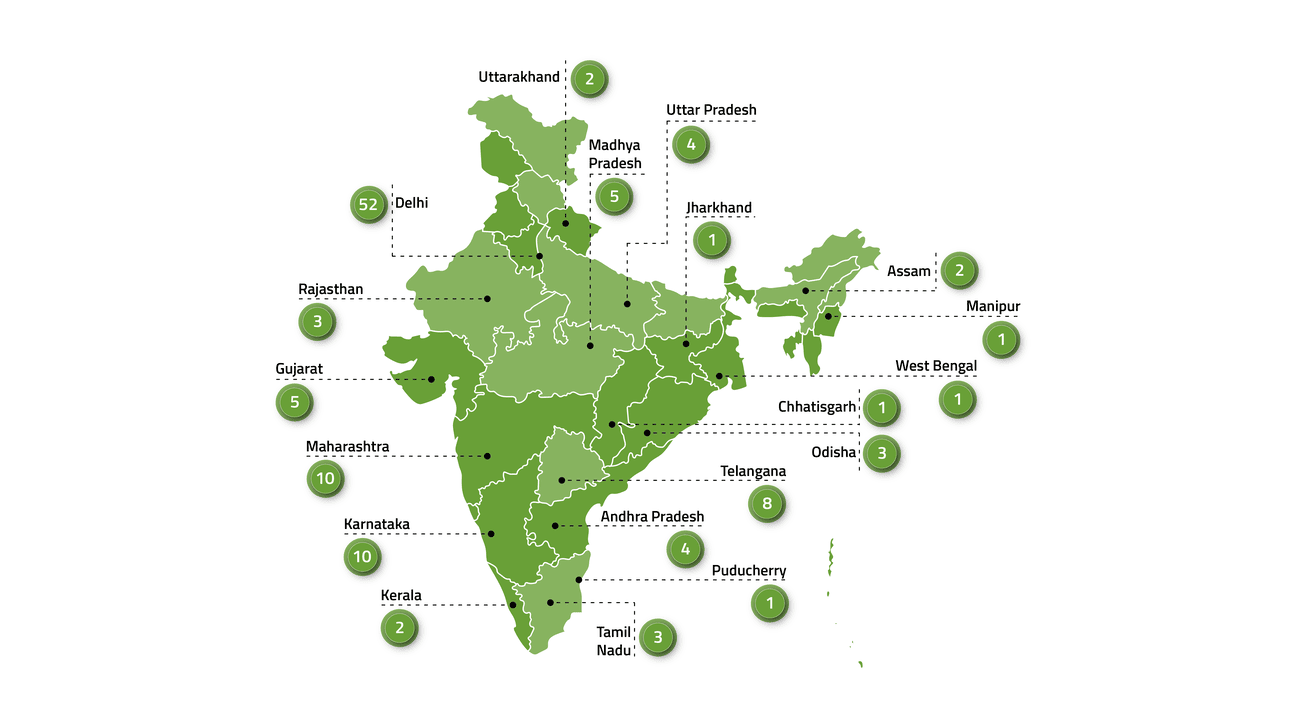

While most farming communities abandoned millets in the decades following the 1970s, some continued cultivating them, and teaching grassroots organizations and activist how to do so. With these insights, NGOs, activists and a handful of academics spearheaded a revival of millets in several parts of the Deccan (south India) and central India, with communities encouraged to cultivate them for their nutritional and ecological benefits.

However, it is the growing popularity of millets among urban elite consumers that has catapulted them to the spotlight. Several popular YouTube channels extol the benefits of these ‘miracle grains’. Food stores in cities and even small towns now stock millet biscuits, vermicelli, and various types of mixes. These products are more expensive than those made from wheat or rice, but consumers are told that the health benefits justify the price difference. Unfortunately, most of these products are made from processed millets and offer only a slight nutritional advantage.

Millets in whole grain form are nutritious, but many of the claims made about them are often exaggerated. For example, many urban consumers and even poor rural families now believe that millets are rich in protein. But just like other cereal grains, millets are not an optimal source of protein. In the past, they were consumed together with protein-rich foods like pulses, meat, buttermilk, oilseeds and fish. Now, millet preparations are often consumed with just vegetables, which does not offer the complete range of nutrients required for a healthy diet. Yet the buzz around millets continues to reverberate, with new government schemes, products and marketing campaigns being launched regularly.

Millets in whole grain form are nutritious, but many of the claims made about them are often exaggerated. For example, many urban consumers and even poor rural families now believe that millets are rich in protein. But just like other cereal grains, millets are not an optimal source of protein. In the past, they were consumed together with protein-rich foods like pulses, meat, buttermilk, oilseeds and fish. Now, millet preparations are often consumed with just vegetables, which does not offer the complete range of nutrients required for a healthy diet. Yet the buzz around millets continues to reverberate, with new government schemes, products and marketing campaigns being launched regularly.

Cautionary tales

Women from DBA communities face the double burden of caste and gender. They carry out most or all of the domestic work in their households in addition to their income-generating activities, which they rarely earn a living wage for. Only a small percentage of women own land. With high levels of migration among men, they are often left to manage the household, livestock and land with little support. Alongside this, they continue to face untouchability practices, even in new structures.

“Whenever our Federation organizes an event, they (dominant caste women) take over the cooking. If you cook, who will eat? That is what they say,” remarked members of a Dalit SHG (Self Help Group).” Until last year, we couldn’t even get a bank loan. All loans went to the other groups.”

SHGs, groups of 15-20 poor women who collectively save and access microcredit, are often cited as the best pathway out of poverty for these women. Through linkages with banks and government programmes, SHG members have accessed loans to buy animals or take up income-generating activities that have enabled them to overcome the barriers to credit they faced as individuals. However, it should be noted that SHGs made up of less poor women (with caste advantages and access to resources) are more likely to succeed in income-generating activities. Most SHGs have instead become a medium to access loans for health, education, and farming-related expenses, and thus fill the gaps left by poorly functioning welfare programmes and insensitive financial institutions.

Grassroots organizations have seized the opportunities generated through SHG-bank linkages to set up millet enterprises, and many have focused their efforts on rural women. These enterprises have the potential to provide economic and nutritional benefits and create long-term rural assets. However, many schemes to alleviate poverty and malnutrition have fallen short because they have neglected systemic issues such as caste discrimination and historical inequities. Further, most millet enterprises are focused on the urban market, which is a risky strategy as urban consumers lack the cultural connection with millets of their rural counterparts and can quickly move on to newer fads. The reintroduction of millets into rural diets is a complex process with uncertain results, but it must be taken up to achieve substantial and long-term improvements in diets and incomes.

Grassroots organizations have seized the opportunities generated through SHG-bank linkages to set up millet enterprises, and many have focused their efforts on rural women. These enterprises have the potential to provide economic and nutritional benefits and create long-term rural assets. However, many schemes to alleviate poverty and malnutrition have fallen short because they have neglected systemic issues such as caste discrimination and historical inequities. Further, most millet enterprises are focused on the urban market, which is a risky strategy as urban consumers lack the cultural connection with millets of their rural counterparts and can quickly move on to newer fads. The reintroduction of millets into rural diets is a complex process with uncertain results, but it must be taken up to achieve substantial and long-term improvements in diets and incomes.

Conclusion

Traditional millet-cultivating communities, which are overwhelmingly Dalit-Bahujan-Adivasi, have had a long and chequered history with millets. This is reflected in the stories told by women from these communities, which reveal the pleasure, trauma, resilience, and innovation associated with cultivating, processing, cooking and consuming these ancient grains. The current popularity of millets presents a golden opportunity to support these women and help them receive some of the benefits from this resurgence. This support should be all-encompassing and intersectional, enduring and adaptable to local issues and ensuring a sustained and responsive approach. We must use this time, when millets are in the spotlight, to share these hidden stories and build structures that truly promote the empowerment of rural women and men. Only then will we honour the sweat, toil and resilience of Kadiramma, Shyamkishori and their sisters.

By Sudha Nagavarapu, Researcher and activist, in collaboration with Native Picture and FOLU India

Photo credit: All rights reserved, Native Picture and FOLU India

Tales of scarcity and resilience

Tales of scarcity and resilience

DBA communities had knowledge of local ecosystems that allowed them to identify edible plants and animals, which they used in unique recipes that are rare to find in popular cookbooks. They also adapted and innovated. While rich and middle-income families roasted chana (Bengal gram) and jau (barley) to make sattu (malt) in the Gangetic plains, poorer families roasted cheaper grains. Today, nutritious foods like browntop millet are attractive to urban consumers, but in the past, they were foraged by DBA communities to stave off hunger.

DBA communities had knowledge of local ecosystems that allowed them to identify edible plants and animals, which they used in unique recipes that are rare to find in popular cookbooks. They also adapted and innovated. While rich and middle-income families roasted chana (Bengal gram) and jau (barley) to make sattu (malt) in the Gangetic plains, poorer families roasted cheaper grains. Today, nutritious foods like browntop millet are attractive to urban consumers, but in the past, they were foraged by DBA communities to stave off hunger. Tales of transformation and aspirations

Tales of transformation and aspirations As incomes rose, DBA households could now afford the foods of the rich—wheat and rice. The grains that they aspired to, which were only consumed on festivals and special occasions, were now accessible due to the Green Revolution. With the expansion of the Public Distribution System (PDS), wheat and rice were supplied at subsidized rates or even free of charge, resulting in a sharp drop in the consumption of millets from the 1970s onward. Even pulses were abandoned. These were cultivated alongside millets, but there was little place for them in the monocropped rice paddies and wheat fields. The diverse diets of DBA communities shrank to rice- and wheat-heavy meals deficient in protein and micronutrients. However, they could now eat to their hearts’ content and weren’t left hungry.

As incomes rose, DBA households could now afford the foods of the rich—wheat and rice. The grains that they aspired to, which were only consumed on festivals and special occasions, were now accessible due to the Green Revolution. With the expansion of the Public Distribution System (PDS), wheat and rice were supplied at subsidized rates or even free of charge, resulting in a sharp drop in the consumption of millets from the 1970s onward. Even pulses were abandoned. These were cultivated alongside millets, but there was little place for them in the monocropped rice paddies and wheat fields. The diverse diets of DBA communities shrank to rice- and wheat-heavy meals deficient in protein and micronutrients. However, they could now eat to their hearts’ content and weren’t left hungry.

Millets in whole grain form are nutritious, but many of the claims made about them are often exaggerated. For example, many urban consumers and even poor rural families now believe that millets are rich in protein. But just like other cereal grains, millets are not an optimal source of protein. In the past, they were consumed together with protein-rich foods like pulses, meat, buttermilk, oilseeds and fish. Now, millet preparations are often consumed with just vegetables, which does not offer the complete range of nutrients required for a healthy diet. Yet the buzz around millets continues to reverberate, with new government schemes, products and marketing campaigns being launched regularly.

Millets in whole grain form are nutritious, but many of the claims made about them are often exaggerated. For example, many urban consumers and even poor rural families now believe that millets are rich in protein. But just like other cereal grains, millets are not an optimal source of protein. In the past, they were consumed together with protein-rich foods like pulses, meat, buttermilk, oilseeds and fish. Now, millet preparations are often consumed with just vegetables, which does not offer the complete range of nutrients required for a healthy diet. Yet the buzz around millets continues to reverberate, with new government schemes, products and marketing campaigns being launched regularly.

Grassroots organizations have seized the opportunities generated through SHG-bank linkages to set up millet enterprises, and many have focused their efforts on rural women. These enterprises have the potential to provide economic and nutritional benefits and create long-term rural assets. However, many schemes to alleviate poverty and malnutrition have fallen short because they have neglected systemic issues such as caste discrimination and historical inequities. Further, most millet enterprises are focused on the urban market, which is a risky strategy as urban consumers lack the cultural connection with millets of their rural counterparts and can quickly move on to newer fads. The reintroduction of millets into rural diets is a complex process with uncertain results, but it must be taken up to achieve substantial and long-term improvements in diets and incomes.

Grassroots organizations have seized the opportunities generated through SHG-bank linkages to set up millet enterprises, and many have focused their efforts on rural women. These enterprises have the potential to provide economic and nutritional benefits and create long-term rural assets. However, many schemes to alleviate poverty and malnutrition have fallen short because they have neglected systemic issues such as caste discrimination and historical inequities. Further, most millet enterprises are focused on the urban market, which is a risky strategy as urban consumers lack the cultural connection with millets of their rural counterparts and can quickly move on to newer fads. The reintroduction of millets into rural diets is a complex process with uncertain results, but it must be taken up to achieve substantial and long-term improvements in diets and incomes.